The Mughal ruler Jahangir had always stated that Lahore was considered as one his favourite cities in northern India. Today Lahore boasts of breath taking gardens such as Shalimar gardens and Jahangir’s tomb with its fountains along with endless mansions and dwellings. During the Sikh period most Mughal structures were hastily occupied by leading Sikh and Muslim courtiers of Maharaja Ranjit Singh when he became sovereign of Lahore in 1801. In this ageless city that has witnessed turbulent upheavals over the centuries are numerous Sikh architectural marvels lying amongst modern day encroachments that the Sikh rulers of Lahore had firmly cemented their indelible footprint in architecture and heritage by promoting arts and culture extensively across the Punjab.

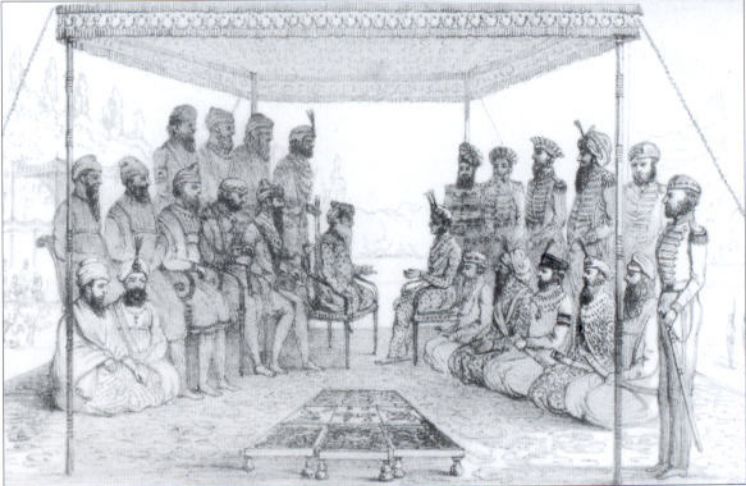

We glimpse in to a dazzling legacy through the systematic rise of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in the early part of the 19th century who had brought comparative peace to a province amidst growing uncertainty, rivalry and grandeur. The Maharaja’s accomplishments are viewed at the most dynamic ever envisaged amongst the native princes to emerge on the Indian subcontinent. In consolidating his supremacy the ‘Lahore Durbar’ or the ‘Court of Lahore’ became a potent hegemony buffered precariously between British India and Afghanistan.

By the 1820’s the territorial boundaries of Ranjit Singh’s empire stretched from Afghanistan in the west to China in the east that British influence had rapidly excelled to the southern fringes of Ranjit Singh’s empire; he responded by modernising his army on a western model in order to meet any potential threat. A variety of Europeans mercenaries were now employed in his armies’ - French, Italian, Hungarian, Spanish, Americans and even English officers were enlisted.

When the Maharaja’s health subsequently deteriorated after he suffered a minor stroke in 1836, factions within the Sikh court began to emerge that the entire administration was firmly in the hands of the omnipotent Raja Dhyan Singh, whose aim was not to safeguard the Sikh kingdom but instead to establish a Dogra Empire. Upon his deathbed in 1839, the ailing Maharaja gathered his senior courtiers to pledge their allegiance to Prince Kharak Singh, his eldest son and successor but proved too feeble to handle the court politics especially the all powerful Dogras. Numerous altercations surfaced between them that Raja Dhyan Singh and Gulab Singh planned a series of schemes to limit the power of the new ruler and palace intrigues simply intensified.

The “Court of Lahore” was now left in deep disarray as various princes and factions vied for control. The game of thrones they played witnessed four more of Ranjit Singh’s sons and descendants dead by 1845. Only the youngest son, Duleep Singh, survived and was declared Maharaja with his mother Rani Jinda taking firm control of court affairs.

The civil and revenue administration had virtually come to a standstill. The collection of revenues except in a few well administered regions had fallen into arrears and district officials had lost their hold on the local civil administration. Furthermore, the Sikh army took liberties by repeatedly demanding more pay and allowances. Such high costs for the troops during 1839-1845, saw the durbar devour the dwindling resources of the state treasury.

Rani Jinda had made her brother Raja Jawahir Singh prime minister but when he became instigated in a murder he was brutally killed by Sikh soldiers in the presence of young Duleep Singh. For this act Rani Jinda vowed to destroy the Sikh army.

With most of the loyal Sikh chiefs murdered, Rani Jinda depended on disgruntled courtiers with administrating court affairs. She was ill-advised and manipulated by Raja Lal Singh who pulled the strings to allow for her machinations while the British provided the opposing force.

But when British troops amassed south of the Sutlej River, it provided a pretext for Rani Jinda to rally the rebellious Sikh soldiers who lay outside the palace gates demanding their salaries. She called on them to protect her husband’s legacy and to defend their homeland against the British.

The British had now despatched spies throughout the Punjab to take stock of the crisis boiling on the Anglo-Sikh frontier. When Sikh troops encamped in enclaves across the Sutlej River recognised as dependencies of the “Lahore Durbar”, it went against the “Treaty of Amritsar” and the British broke all diplomatic relations, the flames of war could not be averted. Sir Hugh Gough marched rapidly towards Ferozepore with over 10,000 men and nearly 40 heavy guns.

On the 18th December the Sutlej campaign was launched with fighting in the village of Mudki, losses on both sides were immense. Days later at Ferozeshah, the battle was one of the hardest fought in the history of the British army in India. Raja Tej Singh commanded the Sikh force of 30,000 men with over 100 heavy guns, but was never a good soldier and marched too slowly. He was joined by Raja Lal Singh who later abandoned the Sikh army on the battlefield. But the brave Khalsa soldiers fought ferociously without their military leaders. Casualties on both sides were huge, British losses amounted to about 1800 and 5000 for the Sikhs.

With the Sikh army suffering defeat after defeat, Rani Jinda sought to prevent the annexation of her kingdom. The British finally declared victory on the 10th February 1846 at Sobraon, and Rani Jina ordered Raja Gulab Singh from Jammu to open negotiations with the Governor-General Lord Hardinge. The British hastily drafted the “Treaty of Lahore” which officially ended the war but reduced the power and territories of Duleep Singh to a third.

A British resident, Sir Henry Lawrence, was installed at Lahore to represent the interests of the East India Company in Punjab. Rani Jinda was awarded an annual pension of 150,000 rupees and replaced by a “Council of Regency” which composed of leading Sikh chiefs acting under the control and guidance of the British Resident, giving the British effective control of the Government.

The following years witnessed the British authorities meddling in the internal affairs of Rani Jinda who resented that her son was now deprived of his sovereign status and authority. Not content with the provisions made to her in the peace treaty, she took the audacious task of challenging the British for improved arrangements as she had the support and sympathy of her people. Veteran Sikh soldiers who had been disbanded did not like Rani Jinda being dishonoured and maltreated by the British. But matters came to the fore when Sir Henry Lawrence sent orders that Rani Jinda’s personal staff be replaced and she be prohibited from meeting her ministers in private without his permission. She became a prisoner in her own palace, and when an attempt was made to remove her to Sheikhupura fort, 25 miles west of Lahore, there was uproar in the populous.

Away from the court, the dismissal of a large number of Sikh soldiers created widespread unrest in the countryside who sought retribution against the British. Rebellion gathered pace and descended into war once again as the British sent in forces under the Punjab campaign to restore order.

On 22 November 1848, at the battle of Ramnagar, it started well for the Sikhs who led a decisive victory guided by Raja Sher Singh who went on to fight the British with zeal and ferociousness at Chillianwala on 13th January 1849. It was seen by the British as their mini Waterloo, with over 2800 men killed and thousands wounded. Sikhs losses were equally high, if not more, and senior soldiers like General Ilahi Bakksh defected to the British side.

The Sikhs were finally defeated at the Battle of Goojerat on the 21st February 1849 and they laid down their arms to General Walter Gilbert who took their formal surrender near Rawalpindi. Later a proclamation was made at the Lahore fort that the Sikh empire had formally ceased and annexed by the British on the 21 March 1849.